“As a military wife, I have an incredibly difficult time using the term PTSD because when I see it or hear it, I automatically think of those men and women in combat who have experienced things that I can’t even imagine.” Katie Banks was responding to my inquiry about whether she thinks she has Post-traumatic Stress resulting from the care of her 7-year-old son, Wyatt. Wyatt has a mutation in the gene SCN8A that causes a number of challenges including intractable epilepsy, autistic-like features, and extreme speech delay.

I interviewed Katie several months ago for the series on PTSD in mothers of medically-fragile children that was published in December on Romper. The series included a reported feature that looked at the limitations in understanding, diagnosing, and treating PTSD in this population, due, in part, to the fact that PTSD symptoms can often be helpful in protecting the life of a child who experiences repeat medical emergencies. It also presented five individual stories of mothers raising children under these circumstances and my own personal story. While the Katie’s full story was not included in the series, it is her story and the ways that she grappled with her traumatic experiences with Wyatt, which keep returning to the front of my mind while I have followed the response to the series. What sticks with me is the fact that Katie recognized that she avoided and inappropriately diminished her feelings, but, at the same time, her loyalty to the veteran community made it difficult for her to use the term Post-traumatic stress to communicate about these experiences.

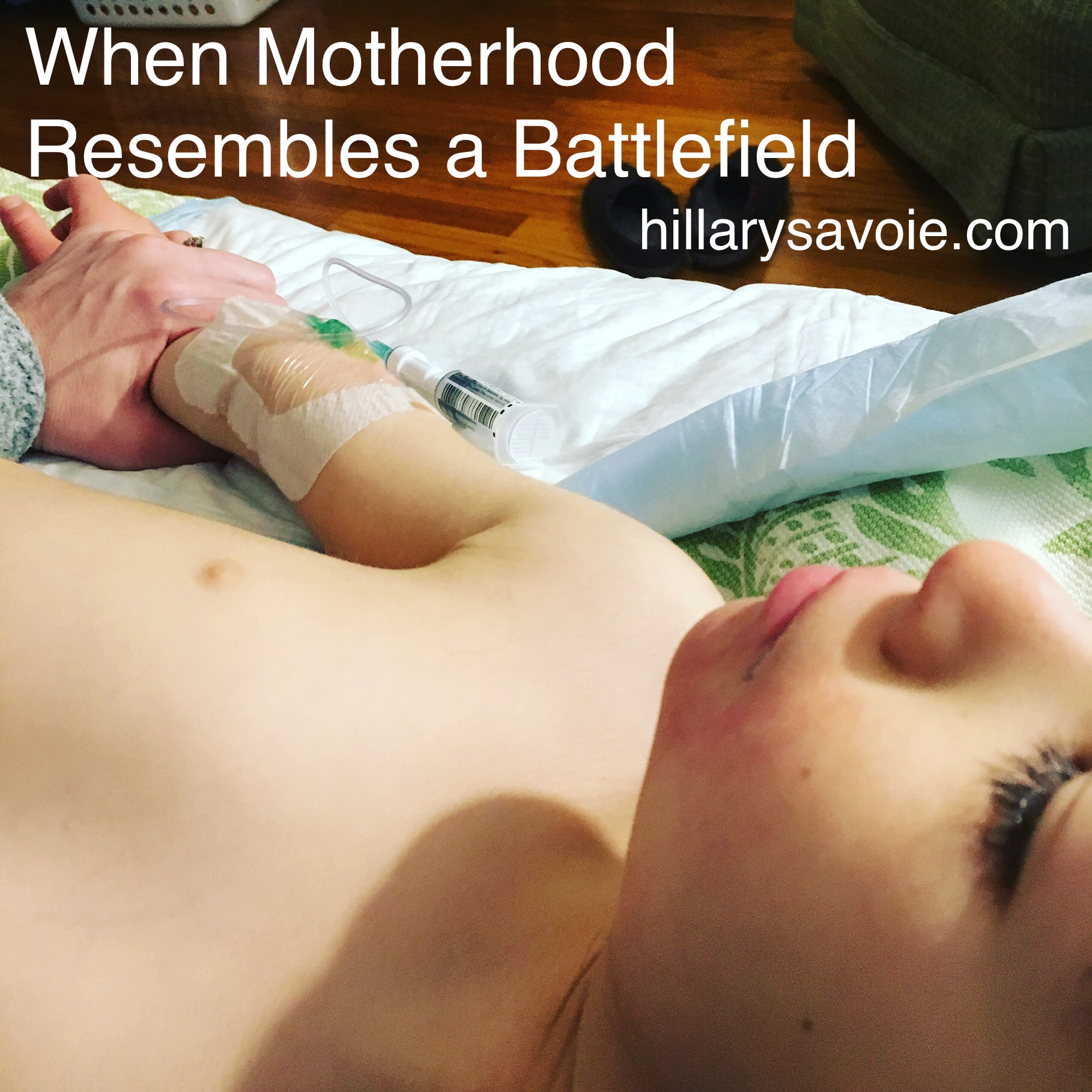

Katie Banks with her son Wyatt

As I explained in the series, studies into the mental health of parent caregivers of any variety are limited, the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders published research showing that mothers raising children with Autism Spectrum Disorder have stress hormone levels that are consistent with those of combat veterans. Yet this concern about labeling an experiences as PTSD, given the connection to the veteran community, was common within the population I interviewed for the series. And, in the weeks since the publication it has been an oft repeated concern as people shared the series and their thoughts. However, in discussions with several combat veterans, I have seen little surprise and zero offense at the notion that a mother caring for a child through repeat life-threatening medical events could produce Post-traumatic Stress. Aaron Gladd, recent candidate for the New York State Senate, Andrew Cuomo’s former Deputy Director of Policy, and combat veteran (Platoon leader, Army, 1st Calvary Division, Afganistan), explained to me, “PTSD isn’t confined to the battlefield, but more and more what we see is that the resources are. I’ve seen PTSD first hand, from both soldiers overseas that I served with, but also families here at home. This issue is much more complex than we sometimes want to admit, but we owe it to our communities – especially our parent caregivers – to better understand and better support one another.”

And while I intensely agree with Gladd about the need to better understand Post-traumatic Stress in the parent caregiver population, it isn’t an easy topic to investigate.

In my almost eight years as a mother of a child with medical-complexities and developmental delay, I have seen the effects of PTSD everywhere in the circle of parents that are my accidental peers: in the fights with medical professionals, the waning connections with family members, the trouble parent-lead advocacy groups faced in collaborating, the struggles orienting to aspects of “typical” life. I also observed it in myself: as I lift my gaze above the heads of small children in order to edit them out. Or as I feel sweat collect on my skin in response to some small sound that calls to mind my child’s gasping blue face.

However, whenever I would start to write about PTSD, I found myself balking. I worried that if I wrote about how much pain I felt from these experiences, people would think I saw my daughter as a burden, rather than the most beautiful light in my life. It felt diminishing of the emergencies that had happened only in front of me, but actually to my daughter. It felt self-indulgent..as if no one would (or should) care. After all, I’d spent years of navigating a medical system that never once asked me how I was coping as a caregiver. I’d also been party to countless conversations that focused on praising me as a “superhero” mom rather than a responsivity to the emotional realities of years straining under that label. I had internalized the idea that my ability to cope (or not) was a subject no one wanted to hear about.

As I began to do some investigation for the story, what I found confirmed this suspicion: There is an all but complete lack of research on this subject of caregivers of children who face life-long, repeating, life-threatening medical traumas. I explored the issue in conversations with major foundations, institutions, and organizations that serve these populations, but often these conversations led to some professional version of a pitying pat on the shoulder and a “here’s the door.” This seemed to be a rock no one wanted turned over.

But, after a point, I couldn’t help myself.

Still what I found was nebulous. I began looking for mothers in the community willing to discuss Post-traumatic Stress. I’d get a message from someone who felt that they might have PTSD, and they would give me a sense of their story. And then they would retreat. Person after person was willing to give these tidbits of their story and encouragement to continue to pursue the topic. However, it was exceedingly difficult to find moms who were willing to engage long enough to share their stories in an interview. They often said they felt their experiences were not extreme enough to count. Or they expressed concern about insulting veterans with Post-traumatic Stress. Or they said they survived by not thinking about their trauma. I knew this made sense, given the symptoms of PTSD—which include, by definition, distorted emotions and avoidance behaviors. I kept at the conversions, however, and, eventually, I found a handful of mothers who were willing to share their stories with me in a series. By the time it was published, in addition to the 5 mothers whose long-form stories are shared in the series, I’d I spoken with over 20 mothers, 4 medical experts, and surveyed dozens of parents in various special needs communities. And I felt as though I was only just cracking the surface.

The response that this story has received in the months since the series was published tells me that this is truer than I could have imagined. The Wall Street Journal recently ran an article on this topic—interviewing me, several other parents, and Dr. Katherine Junger, the clinical psychologist who was included in the Romper report. The quietly kept open secret of trauma in the parenting communities of children with devastating disorders needs, desperately, to be discussed further. I’ve followed post after post on social media of moms saying that these stories are theirs too, that they had been afraid to articulate their feelings of helplessness and isolation, it seems clear that there were so people just waiting for permission to open the dialogue.

These stories are not isolated, and they are also not without cost. A recent PLOS One paper showed that mothers raising children with autism spectrum and intellectual disabilities, without additional medical challenges, have significantly higher mortality rates than their peers—significantly higher risks of death associated with cardiovascular disease, homicide, suicide, and accident. With the survival rates of children with significant medical and developmental challenges increasing, due to the improvement in the quality of medical care as well as increase in maternal age, the realities of the cost of PTSD to parent caregivers’ mental and physical health is not negligible. Also, not negligible is the fact that it is these very caregivers, working as volunteers, who are often pulling the lion’s share of advocacy efforts in rare disease research funding, legislative action, and healthcare policy. Without the labor of this community, we would see a substantial diminishment in the rate of medical research, the speed of availability of life-saving treatments, and comprehensive healthcare coverage—from which we all benefit.

We are a society that is currently obsessed by the feel-good stories of around disability that cast people as superheroes in inspiration-porn. Meanwhile, we also seem to be turning away from the realities that threaten the well-being of these same people, afraid to face the truth that parents like those in this series are just humans who are not particularly well-prepared for the obstacles our children face, and that we need help. And we need it soon before we buckle under the weight of everything—from leading the quest for cures, to providing exceptional care for our children, to advocating for change, to educating the systems we rely upon, to inspiring everyone around us—that has been placed on our shoulders to carry, alone.

And that all begins with the difficult task of talking about it.